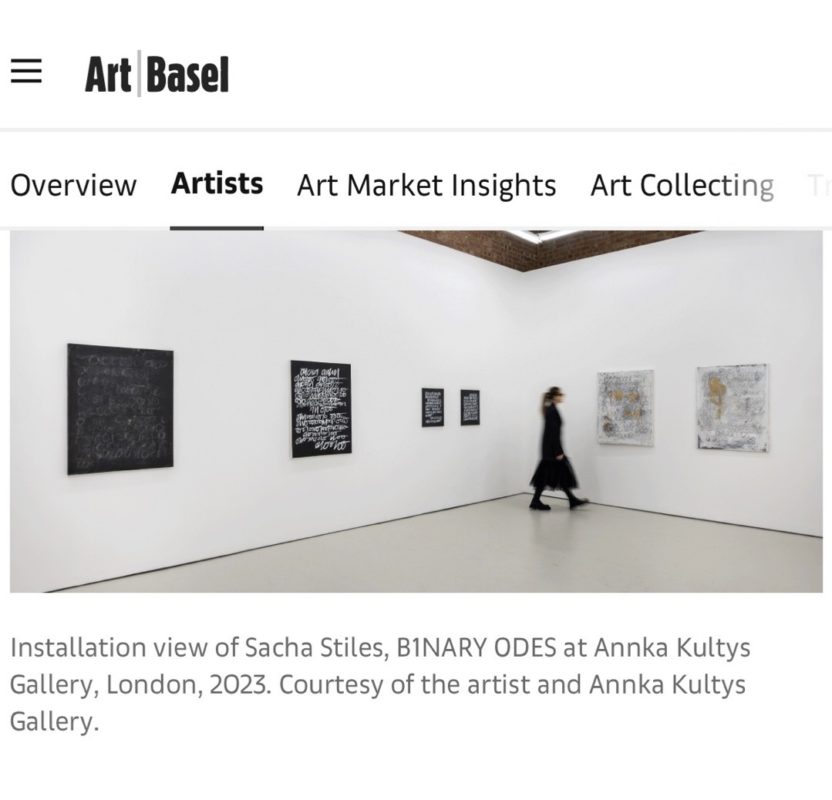

Annka Kultys founded her eponymous gallery in London in 2015 with the explicit aim of supporting digital and new-media artists who work with emerging technologies. The 2021 show AI Portraiture: Us and Them was a survey that offered ‘commentary about how AI sees us and how we see AI’, according to Kultys. It featured practitioners as diverse as the somewhat gimmicky Ai-Da robot to the critically acclaimed avatar artist and curator LaTurbo Avedon. The show also tapped into AI’s playful, crowd-pleasing side with works like Thomas Webb’s You can’t afford it (2020), which fed images of the visitor into an algorithm that had allegedly been trained to decide how rich someone is based on their appearance. For the conceptual artist Jonas Lund’s exhibition In the Middle of Nowhere II (2023), potted plants and office furniture were installed to give the gallery a more clinical, corporate atmosphere. The walls were covered in AI-generated tapestries filled with unnerving images of literal fat cats and pigs in suits around conference tables. The work uses a once-venerated traditional textile craft medium to explore our anxieties about where an AI-driven world might be headed.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kultys launched the online platform [The art happens here] as she became increasingly interested in how to show digitally native art in its ‘natural habitat’. One of the exhibitions featured was pseudonymous artist Bill Poster’s Dissimilation, which contained two video compilations featuring AI-generated deepfakes of prominent public figures Kim Kardashian, Morgan Freeman and Mark Zuckerberg, each convincingly delivering invented monologues that expose the growing threat of data exploitation and disinformation. Every one of these shows included in the online programme is essentially ‘ongoing’, because they can still be accessed at any time.

By 2022 it seemed obvious to Kultys that having a separate physical and digital exhibition programme was limiting her options. She collaborated with specialist developers at GalleriesNow to produce a ‘phygital’ gallery that could instead be accessed via virtual reality (VR). She recalled how the company’s co-founder Tristram Fetherstonhaugh promised her, ‘instead of scrolling the space, you’ll be strolling the space’. Keen to encourage people to also experience the works in person, Kultys does not share a link to view the virtual gallery online but instead supplies the necessary VR headsets in house.

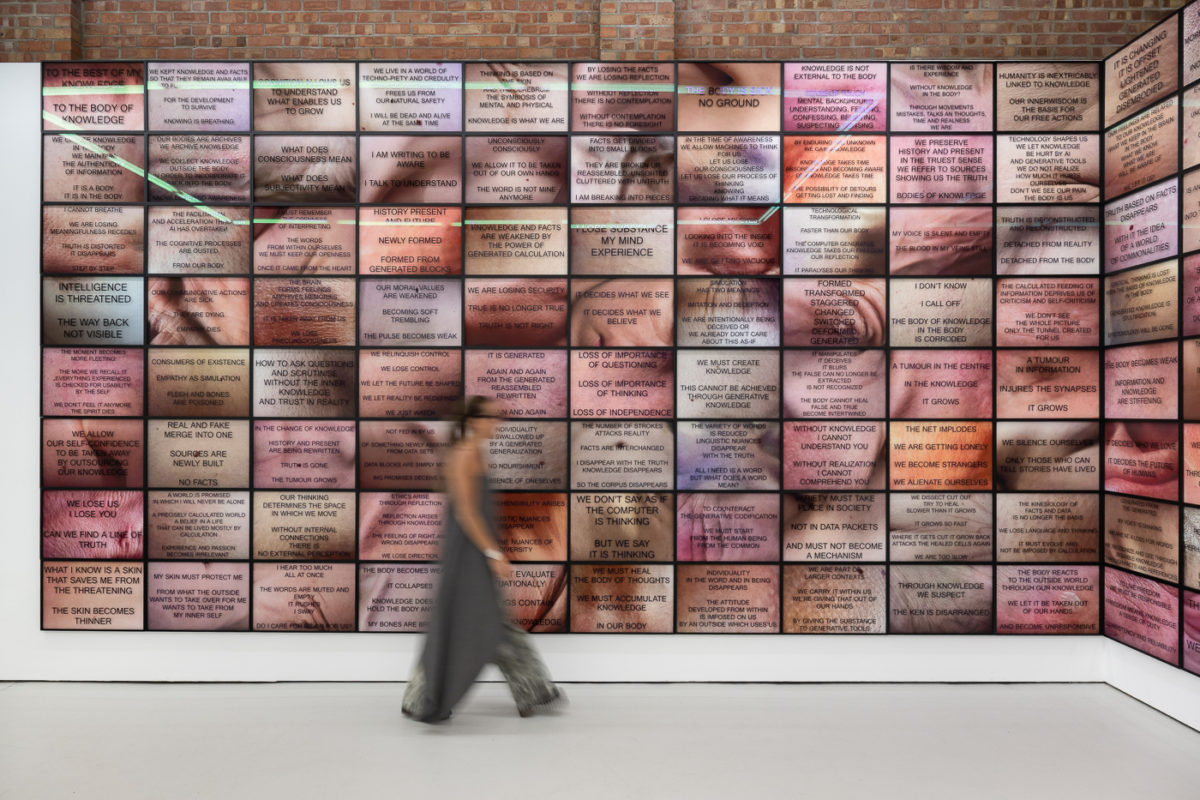

The experience is vulnerable to the whims of the internet and other unexpected technical hitches, but, when in working order, the visitor is transported to a virtual version of Kultys’s bricks-and-mortar gallery. Whereas the real space inhabits a former storage unit in a rough-around-the-edges corner of London’s East End, the virtual gallery is a much larger complex. The exhibition is staged inside a central pavilion, which is situated within a wider complex of gallery spaces arranged like alcoves around a square courtyard. While the real, physical gallery is topped by corrugated industrial roofing sheets, the open-air VR version allows visitors to gaze up at an always-blue sky. ‘I feel like my gallery is finally complete,’ says Kultys. ‘My dream gallery would have been to have LED screens all over it, and the VR gallery replicates this immersive effect.’ She also noted that it is more affordable.

The hybrid ‘phygital’ approach has come to define Kultys’s curatorial vision. She had never liked the clunky screens that began proliferating throughout galleries after the NFT boom of 2021. Aside from being unseemly, they each required a specific aspect ratio. By contrast, the ‘screens’ that blanket the walls of the virtual gallery spaces are adaptable to any kind of image format. The central space can also be used to stage 3D digital sculptures, allowing these to be experienced in the round. ‘We present the digital work as it was made by the artist,’ says Kultys.